Introduction

Direction finding is an important but often overlooked skill, both in real life and scouting life. The ability to know where you are and where you are going can be potentially lifesaving. This section aims to address part of the 'where you are going' problem. If you want to find related material then check out the Map and Compass sections of Scouting Resources.

There are many methods of direction finding, perhaps the most commonly known being the magnetic compass. However, there are methods that are easier and quicker than this (for rough direction finding) and methods that do not rely upon you having any special materials at all (other than the use of your eyesight).

Astronomical Pointers

Astronomical pointers have been the basis of navigation for centuries and can still play a major part in navigation across the globe.

Simple to learn and easy to apply they can prove useful in almost any situation (as long as you can actually see the stars!)

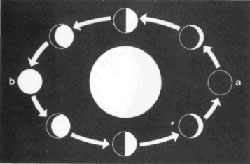

The Moon

The Moon has no light of its own, it reflects that of the sun. As it orbits the Earth over 28 days the shape of the light reflected varies according to its position. When the Moon is on the same side of the Earth as the Sun no light is visible - this is the 'new moon' (a) - then it reflects light froms its apparent right-hand side, from a gradually increasing area as it 'waxes'. At the full moon is it on the opposite side of the Earth from the Sun (b) and then it 'wanes', the reflecting area gradually reducing to a narrow sliver on the apparent left-hand side. This can be used to identify direction.If the Moon rises BEFORE the Sun has set the illuminated side will be on the west.

If the Moon rises AFTER midnight the illuminated side will be in the east. This may seem a little obvious, but it does mean you have the Moon as a rough east-west reference during the night.

The Northern Sky

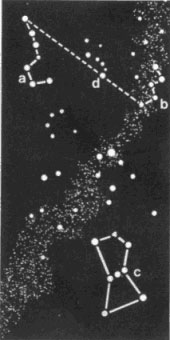

The main constellations to learn are the Plough, also known as the Big Dipper (a), Cassiopeia (b) and Orion (c), all of which, like all stars in the northern sky, apparently circle the pole star (d), but the first two are recognizable groups that do not set.

These constellations come up at different times according to latitude and Orion is most useful if you are near the Equator.

Each can be used in some way to check the position of the pole star, but once you have learned to recognize it you probably will not need to check each time.

A line can be drawn connecting Cassiopeia and the Plough through the Pole Star. You will notice that the two lowest stars of the Great Bear (as shown here) point almost to the Pole Star. It will help you to find these constellations if you look along the Milky Way, which stretches right across the sky, appearing as a hazy band of millions of stars.

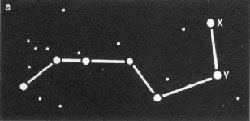

Plough (Big Dipper)

The plough is the central feature of a very large constellation, the Great Bear (Ursa Major). It wheels around the Pole Star. The two stars Dubhe (x) and Merak (y) point, beyond Dubhe, almost exactly to the Pole Star about four times further away than the distance between them

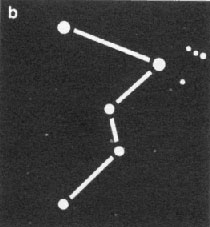

Cassiopeia

Cassiopeia is shaped like a W and also wheels around the North Star. It is on the opposite side of the Pole Star and about the same apparent distance away as the Plough.

On clear, dark nights this constellation may be observed overlaying the Milky Way. It is useful to find this constellation as a guide to the location of the Pole Star, if the Plough is obscured for some reason. The centre star points almost directly towards it.

Orion

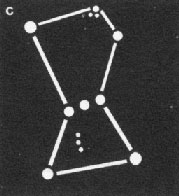

Orion rises above the Equator and can be seen in both hemispheres. It rises on its side, due east, irrespective of the observer's latitude, and sets due west. Mintaka (a) is directly above the Equator. Orion appears further away from the Pole Star than the previous constellations. He is easy to spot by the three stars forming his belt, and the lesser stars forming his sword.

Other Stars

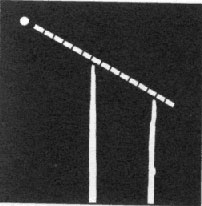

Other stars that rise and set can be used to determine direction. Set two stakes in the ground, one shorter than the other, so that you can sight along them. Looking along them at any star - except the Pole Star - it will appear to move. From the star's apparent movement you can deduce the direction in which you are facing.

- Apparently Rising = facing east

- Apparently falling = facing west

- Looping flatly to the right = facing south

- Looping flatly to the left = facing north

These are only approximate directions but you will find them adequate for navigation. They will be reversed in the Southern Hemisphere.

Southern Sky

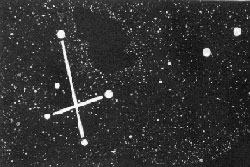

There is no star near the South Celestial Pole bright enough to be easily recognised. Instead a prominent constellation is used as a signpost to south: the Southern Cross (Crux) a constellation of five stars which can be distinguished from two other cross shaped groups by its size - it is smaller - and its two pointer stars.

One way to find the Southern Cross is to look along the Milky Way, the band of millions of distant stars that can be seen running across the sky on a clear night. In the middle of it there is a dark patch where a cloud of dust blocks out the bright star background, known as the Coal Sack. On one side of it is the Southern Cross, on the other the two bright pointer stars.

Finding South

To locate south project an imaginary line along the cross and four and a half times longer and then drop it vertically down to the horizon. Fix, if you can, a prominent landmark on the horizon - or drive two sticks into the ground to enable you to remember the position by day.

Shadow Stick

The Earth's revolution on its axis produces the changes from light to darkness and its orbit around the sun produces the seasons (Note: NOT because of the distance to the sun. In actual fact, the earth is closest to the sun during the winter months). The earth is tilted at an angle to the sun and first the north and then the south becomes nearer to it, the closest point traversing from the Tropic of Cancer (23.5° N) to the Tropic of Capricorn (23.5° S), the sun being above Cancer on 22 June and above Capricorn on 22 December. It is above the Equator on 21 March and 21 September.

The sun rises in the east and sets in the west - but not EXACTLY in the east and west. Indeed there is a seasonal variation. In the Northern Hemisphere, when at its highest point in the sky, the sun will be due south; in the Southern Hemisphere this noonday point will mark due north. The hemisphere will be indicated by the way that shadows move; clockwise in the north, anticlockwise in the south. Shadows can be a guide to both direction and time of day.

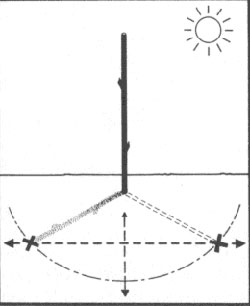

Shadow Stick Method

A resonably accurate, if time consuming, method is to mark the first shadow tip in the morning. Draw a clean arc at exactly this distance from the stick, using the stick as a centre point. As midday approaches the shadow will shrink and move. In the afternoon, as the shadow lengthens again, mark the EXACT spot where it touches the arc. Join the two points to give east and west. West is the morning mark.

At local Noon the shadow will actually point due North (note this is assuming you are in the Northern Hemisphere and that it is LOCAL noon, something that may be difficult to note unless you know your location, something of a catch 22 situation)

Watch

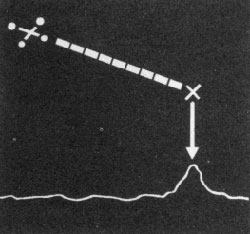

A traditional watch with two hands can be used to find direction, provided it is set to true local time (without variation for summer daylight saving and ignoring conventional time zones which do not match real time). The nearer the Equator you are the less accurate this method will be, for with the sun almost directly overhead it is very difficult to determine its direction.

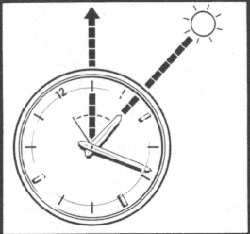

Northern Hemisphere

Hold the watch horizontal. Point the hour hand at the sun. Bisect the angle between the hour hand and the 12 mark to give a north- south line.

South will be in the direction of the arrow shown on the diagram to the right (in between the hour hand and the 12 mark).

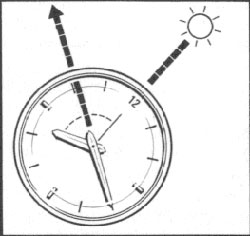

Southern Hemisphere

Hold the watch horizontal. Point 12 towards the sun. A mid-point between 12 and the hour hand will give you the north-south line.

North will be in the direction of the arrow shown on the diagram to the right (in between the hour hand and the 12 mark).

Improvised Compasses

A piece of ferrous metal wire (a sewing needle is ideal) stroked repeatedly in one direction against silk will become magnetized and can be suspended so that it points north. The magnetism will not be strong and will need regular topping up.

Suspend the needle in a loop of thread, so that it does not affect the balance. Any kinks in or twisting of the thread must be avoided.

Stroking with a magnet, should you have one, will be much more efficient than using silk. Stroke the metal smoothly from one end to the other in one direction only.

A suspended needle will be easier to handle on the move but in camp or when making a halt a better method is to lay the needle on a piece of paper, bark or grass and float it on the surface of water.

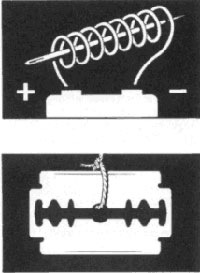

Electricity/Razor Blade

If you have a power source of two volts or more (a small dry battery, for instance) the current can be used to magnetize the metal. You will also need a short length of wire, preferably insulated. Coil the insulated wire around the 'needle':If it has no ready-made insulation wrap a few layers of paper or a piece of cardboard around the needle first. Attach the ends of the wire to the terminals of the battery for five minutes.

A thin flat razor blade can make a good improvised compass. Apart from stroking it with a magnet it is claimed by some people that it can be magnetized simply by stropping WITH CARE against the palm of the hand. SR would be interested in hearing from anyone who has managed to make this method work. To ensure that the stropping is responsible please carefully ensure that the razor was not in the least bit magnetized before it was stropped.

Wind Direction

If the wind direction of the prevailing wind is known it can be used for maintaining direction - there are consistent patterns throughout the world but they are not always the same the whole year round.

Where a strong wind always comes from the same direction plants and trees may be bent in one direction, clear evidence of the wind's orientation. But plants are not the only indication of wind direction: birds and insects will usually build their nests in the lee of any cover and spiders cannot spin their webs in the wind. Snow and sand dunes are also blown into distinctive patterns by a prevailing wind which blows from the outside of the high central ridges.

Plant Pointers

Compass Plant of North America directs its leaves in a north-south alignment. Its profile from east or west is quite different from that of north or south.

North Pole Plant which grows in South Africa, leans towards the north to gain full advantage of the sun.

Even without a compass or the sun to give direction you can get an indication of north and south from plants. They tend to grow towards the sun so their flowers and most abundant growth will be to the south in the Northern Hemisphere, the north in the South.

On tree trunks moss will tend to be greener and more profuse on that side too (on the other side it will be yellowish to brown). Trees with a grainy bark will also display a tighter grain on the north side of the tree trunk.

If trees have been felled or struck down the pattern of the rings on the stump also indicates direction - more growth is made on the side towards the Equator so there the rings are more widely spaced. There are even species of plant known for their north-south orientation.